José Bénazéraf's La nuit la plus longue (1965) is about antagonism in all its forms, from gentle and passive to confrontational and violent. From its simple theme to its simple premise, a kidnapping by a group of four of a young woman, the daughter of a wealthy man, held for ransom to its simple setting, a secluded house out in the country, with its events playing out over the course of one evening (and hence the title). With simplicity and singularity taking care of most of his film, Bénazéraf can play with his characters, his images, and the emotions.

"Une bande de petits truands y sequestre la nana dans une maison isolee, esperant la rancon prevue pour le lendemain matin, L'angoisse de l'attente de l'aube, l'insondable profondeur de la nuit, son silence, exasperent la tension grandissante, trouvant ici encore son aboutissement dans un denouement dramatique. Jose Benazeraf y est lui-meme spectateur d'une tres excitante danse sapho-masochiste de deux creatures denudees, l'une feminine et se caressant elle-meme, l'autre hermaphrodite, la dominant, jouant avec elle, et la soumettant a son fouet." (from Anthologie Permanente de l'Erotisme au Cinema José Bénazéraf by Paul Herve Mathis and Anna Angel, ed. Eric Losfeld, Le Terrain Vague, Paris, France, 1973)

"Une bande de petits truands y sequestre la nana dans une maison isolee, esperant la rancon prevue pour le lendemain matin, L'angoisse de l'attente de l'aube, l'insondable profondeur de la nuit, son silence, exasperent la tension grandissante, trouvant ici encore son aboutissement dans un denouement dramatique. Jose Benazeraf y est lui-meme spectateur d'une tres excitante danse sapho-masochiste de deux creatures denudees, l'une feminine et se caressant elle-meme, l'autre hermaphrodite, la dominant, jouant avec elle, et la soumettant a son fouet." (from Anthologie Permanente de l'Erotisme au Cinema José Bénazéraf by Paul Herve Mathis and Anna Angel, ed. Eric Losfeld, Le Terrain Vague, Paris, France, 1973)

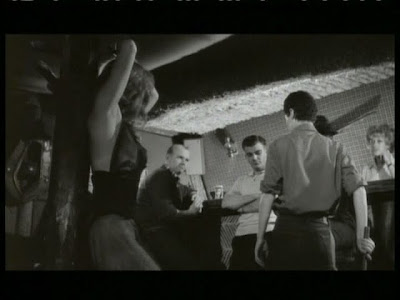

As soon as the group's victim, Virginie (Virginie Solenn), arrives at the house, she lashes out upon one, Carl (Yves Duffaut), by raking her nails down his cheeks. He hits her and knocks her out, and Pierre (Alain Tissier) takes her upstairs to the bedroom. Pierre descends the stairs, looking tired or either bored, sits at the table and Carl has a bit of fun by pointing a pistol at his face. Pierre turns to the sound of music and watches the boss's mistress (Annie Josse) dancing in the corner, seemingly uncaring and unaware as to what is going on around her.

As soon as the group's victim, Virginie (Virginie Solenn), arrives at the house, she lashes out upon one, Carl (Yves Duffaut), by raking her nails down his cheeks. He hits her and knocks her out, and Pierre (Alain Tissier) takes her upstairs to the bedroom. Pierre descends the stairs, looking tired or either bored, sits at the table and Carl has a bit of fun by pointing a pistol at his face. Pierre turns to the sound of music and watches the boss's mistress (Annie Josse) dancing in the corner, seemingly uncaring and unaware as to what is going on around her.  La nuit la plus longue benefits from its simplicity. Bénazéraf plays with tension as a jazz musician would with tempo. The look on Tissier's Pierre's face when he sees the cute young woman dancing alone reads that it's going to be a truly long night. His character is focal, and any emotion within him is the catalyst for the film's action. Bénazéraf doesn't reserve mixing emotions solely with Pierre, however. In one of the film's most provocative scenes (and there are quite a few of them), François (Willy Braque), the group's boss, arrives, notices that Virginie is captive, and seems content that she's a quiet and docile hostage. A can of beer won't pass the time for François, so he pulls his knife from his pocket and in teasing tosses it inches from Pierre's face. Pierre doesn't react, because he's either indifferent or scheming or suppressing his anger. (Bénazéraf lets the viewer pick any of those three choices as any is possible). François pulls another knife from his pocket and approaches his mistress, and as she stands still and calm, he begins to cut the buttons away from the back of her blouse, eventually disrobing her in front of all. The use of the weapon and the stillness of his mistress are an uncomfortable blend of fear and eroticism, as if the scene could take a turn into violence. Likewise, this performance could just be this couple's kink: a little show for everyone, just to turn the two on.

La nuit la plus longue benefits from its simplicity. Bénazéraf plays with tension as a jazz musician would with tempo. The look on Tissier's Pierre's face when he sees the cute young woman dancing alone reads that it's going to be a truly long night. His character is focal, and any emotion within him is the catalyst for the film's action. Bénazéraf doesn't reserve mixing emotions solely with Pierre, however. In one of the film's most provocative scenes (and there are quite a few of them), François (Willy Braque), the group's boss, arrives, notices that Virginie is captive, and seems content that she's a quiet and docile hostage. A can of beer won't pass the time for François, so he pulls his knife from his pocket and in teasing tosses it inches from Pierre's face. Pierre doesn't react, because he's either indifferent or scheming or suppressing his anger. (Bénazéraf lets the viewer pick any of those three choices as any is possible). François pulls another knife from his pocket and approaches his mistress, and as she stands still and calm, he begins to cut the buttons away from the back of her blouse, eventually disrobing her in front of all. The use of the weapon and the stillness of his mistress are an uncomfortable blend of fear and eroticism, as if the scene could take a turn into violence. Likewise, this performance could just be this couple's kink: a little show for everyone, just to turn the two on. Bénazéraf's piece de resistance comes from his love of the image and sensuality and rebellion. "For Bénazéraf eroticism is revolutionary. 'In bourgeois society eroticism is a form of anarchy.'" (from Immoral Tales: European Sex and Horror Movies 1956-1984 by Cathal Tohill and Pete Tombs, St. Martin's Griffin Press, New York, 1995.) Bénazéraf and the viewer get treated to a performance while the on-screen viewers relax: a willing performance in front of a willing audience from a wilful film maker. A play on masculine/feminine and dominant/submissive, two females dance, one with whip in hand, donning tight blue jeans and a button-down shirt, while the other, barely clothed in sheer fabric pieces and a thong. As the two disrobe each other while they dance, their performance is playful, unreal violence, role-playing, and titillation. The sequence brilliantly lacks almost all narrative weight, thinly segued into the film, and exists only to be provocative. The sequence also houses La nuit's best use of audio as the music from the dancing sequence overlaps with love scenes between Tissier and Solenn: rhythmic beats, wilful silence, and some jazz riffs from Chet Baker.

Bénazéraf's piece de resistance comes from his love of the image and sensuality and rebellion. "For Bénazéraf eroticism is revolutionary. 'In bourgeois society eroticism is a form of anarchy.'" (from Immoral Tales: European Sex and Horror Movies 1956-1984 by Cathal Tohill and Pete Tombs, St. Martin's Griffin Press, New York, 1995.) Bénazéraf and the viewer get treated to a performance while the on-screen viewers relax: a willing performance in front of a willing audience from a wilful film maker. A play on masculine/feminine and dominant/submissive, two females dance, one with whip in hand, donning tight blue jeans and a button-down shirt, while the other, barely clothed in sheer fabric pieces and a thong. As the two disrobe each other while they dance, their performance is playful, unreal violence, role-playing, and titillation. The sequence brilliantly lacks almost all narrative weight, thinly segued into the film, and exists only to be provocative. The sequence also houses La nuit's best use of audio as the music from the dancing sequence overlaps with love scenes between Tissier and Solenn: rhythmic beats, wilful silence, and some jazz riffs from Chet Baker.

Perhaps the sexiest thing about La nuit la plus longue, beyond its playfulness, provocative nature, and jazzy structure, is its genuineness. Few film makers are real rebels like Bénazéraf.

Perhaps the sexiest thing about La nuit la plus longue, beyond its playfulness, provocative nature, and jazzy structure, is its genuineness. Few film makers are real rebels like Bénazéraf.

"Une bande de petits truands y sequestre la nana dans une maison isolee, esperant la rancon prevue pour le lendemain matin, L'angoisse de l'attente de l'aube, l'insondable profondeur de la nuit, son silence, exasperent la tension grandissante, trouvant ici encore son aboutissement dans un denouement dramatique. Jose Benazeraf y est lui-meme spectateur d'une tres excitante danse sapho-masochiste de deux creatures denudees, l'une feminine et se caressant elle-meme, l'autre hermaphrodite, la dominant, jouant avec elle, et la soumettant a son fouet." (from Anthologie Permanente de l'Erotisme au Cinema José Bénazéraf by Paul Herve Mathis and Anna Angel, ed. Eric Losfeld, Le Terrain Vague, Paris, France, 1973)

"Une bande de petits truands y sequestre la nana dans une maison isolee, esperant la rancon prevue pour le lendemain matin, L'angoisse de l'attente de l'aube, l'insondable profondeur de la nuit, son silence, exasperent la tension grandissante, trouvant ici encore son aboutissement dans un denouement dramatique. Jose Benazeraf y est lui-meme spectateur d'une tres excitante danse sapho-masochiste de deux creatures denudees, l'une feminine et se caressant elle-meme, l'autre hermaphrodite, la dominant, jouant avec elle, et la soumettant a son fouet." (from Anthologie Permanente de l'Erotisme au Cinema José Bénazéraf by Paul Herve Mathis and Anna Angel, ed. Eric Losfeld, Le Terrain Vague, Paris, France, 1973) As soon as the group's victim, Virginie (Virginie Solenn), arrives at the house, she lashes out upon one, Carl (Yves Duffaut), by raking her nails down his cheeks. He hits her and knocks her out, and Pierre (Alain Tissier) takes her upstairs to the bedroom. Pierre descends the stairs, looking tired or either bored, sits at the table and Carl has a bit of fun by pointing a pistol at his face. Pierre turns to the sound of music and watches the boss's mistress (Annie Josse) dancing in the corner, seemingly uncaring and unaware as to what is going on around her.

As soon as the group's victim, Virginie (Virginie Solenn), arrives at the house, she lashes out upon one, Carl (Yves Duffaut), by raking her nails down his cheeks. He hits her and knocks her out, and Pierre (Alain Tissier) takes her upstairs to the bedroom. Pierre descends the stairs, looking tired or either bored, sits at the table and Carl has a bit of fun by pointing a pistol at his face. Pierre turns to the sound of music and watches the boss's mistress (Annie Josse) dancing in the corner, seemingly uncaring and unaware as to what is going on around her.  La nuit la plus longue benefits from its simplicity. Bénazéraf plays with tension as a jazz musician would with tempo. The look on Tissier's Pierre's face when he sees the cute young woman dancing alone reads that it's going to be a truly long night. His character is focal, and any emotion within him is the catalyst for the film's action. Bénazéraf doesn't reserve mixing emotions solely with Pierre, however. In one of the film's most provocative scenes (and there are quite a few of them), François (Willy Braque), the group's boss, arrives, notices that Virginie is captive, and seems content that she's a quiet and docile hostage. A can of beer won't pass the time for François, so he pulls his knife from his pocket and in teasing tosses it inches from Pierre's face. Pierre doesn't react, because he's either indifferent or scheming or suppressing his anger. (Bénazéraf lets the viewer pick any of those three choices as any is possible). François pulls another knife from his pocket and approaches his mistress, and as she stands still and calm, he begins to cut the buttons away from the back of her blouse, eventually disrobing her in front of all. The use of the weapon and the stillness of his mistress are an uncomfortable blend of fear and eroticism, as if the scene could take a turn into violence. Likewise, this performance could just be this couple's kink: a little show for everyone, just to turn the two on.

La nuit la plus longue benefits from its simplicity. Bénazéraf plays with tension as a jazz musician would with tempo. The look on Tissier's Pierre's face when he sees the cute young woman dancing alone reads that it's going to be a truly long night. His character is focal, and any emotion within him is the catalyst for the film's action. Bénazéraf doesn't reserve mixing emotions solely with Pierre, however. In one of the film's most provocative scenes (and there are quite a few of them), François (Willy Braque), the group's boss, arrives, notices that Virginie is captive, and seems content that she's a quiet and docile hostage. A can of beer won't pass the time for François, so he pulls his knife from his pocket and in teasing tosses it inches from Pierre's face. Pierre doesn't react, because he's either indifferent or scheming or suppressing his anger. (Bénazéraf lets the viewer pick any of those three choices as any is possible). François pulls another knife from his pocket and approaches his mistress, and as she stands still and calm, he begins to cut the buttons away from the back of her blouse, eventually disrobing her in front of all. The use of the weapon and the stillness of his mistress are an uncomfortable blend of fear and eroticism, as if the scene could take a turn into violence. Likewise, this performance could just be this couple's kink: a little show for everyone, just to turn the two on. Bénazéraf's piece de resistance comes from his love of the image and sensuality and rebellion. "For Bénazéraf eroticism is revolutionary. 'In bourgeois society eroticism is a form of anarchy.'" (from Immoral Tales: European Sex and Horror Movies 1956-1984 by Cathal Tohill and Pete Tombs, St. Martin's Griffin Press, New York, 1995.) Bénazéraf and the viewer get treated to a performance while the on-screen viewers relax: a willing performance in front of a willing audience from a wilful film maker. A play on masculine/feminine and dominant/submissive, two females dance, one with whip in hand, donning tight blue jeans and a button-down shirt, while the other, barely clothed in sheer fabric pieces and a thong. As the two disrobe each other while they dance, their performance is playful, unreal violence, role-playing, and titillation. The sequence brilliantly lacks almost all narrative weight, thinly segued into the film, and exists only to be provocative. The sequence also houses La nuit's best use of audio as the music from the dancing sequence overlaps with love scenes between Tissier and Solenn: rhythmic beats, wilful silence, and some jazz riffs from Chet Baker.

Bénazéraf's piece de resistance comes from his love of the image and sensuality and rebellion. "For Bénazéraf eroticism is revolutionary. 'In bourgeois society eroticism is a form of anarchy.'" (from Immoral Tales: European Sex and Horror Movies 1956-1984 by Cathal Tohill and Pete Tombs, St. Martin's Griffin Press, New York, 1995.) Bénazéraf and the viewer get treated to a performance while the on-screen viewers relax: a willing performance in front of a willing audience from a wilful film maker. A play on masculine/feminine and dominant/submissive, two females dance, one with whip in hand, donning tight blue jeans and a button-down shirt, while the other, barely clothed in sheer fabric pieces and a thong. As the two disrobe each other while they dance, their performance is playful, unreal violence, role-playing, and titillation. The sequence brilliantly lacks almost all narrative weight, thinly segued into the film, and exists only to be provocative. The sequence also houses La nuit's best use of audio as the music from the dancing sequence overlaps with love scenes between Tissier and Solenn: rhythmic beats, wilful silence, and some jazz riffs from Chet Baker.

Perhaps the sexiest thing about La nuit la plus longue, beyond its playfulness, provocative nature, and jazzy structure, is its genuineness. Few film makers are real rebels like Bénazéraf.

Perhaps the sexiest thing about La nuit la plus longue, beyond its playfulness, provocative nature, and jazzy structure, is its genuineness. Few film makers are real rebels like Bénazéraf.

1 comment:

Thanks for the excellent grabs.

Those compositions are striking.

I'm getting more and more intrigued by José Bénazéraf's work.

Post a Comment